You are here

Worldwatch Nourishing Planet Interview - Extended

Worldwatch Nourishing Planet Interview Questions for Seth Itzkan

http://blogs.worldwatch.org/nourishingtheplanet/

- From your perspective, what is holistic livestock management and how does this idea challenge conventional grazing systems?

- What are the indicators for improved ecosystem health under holistic management techniques?

- Why is holistic management significant to the issues of desertification and climate change mitigation and adaptation?

- Using cattle to mitigate global warming might seem counter-intuitive to many, especially in light of estimates that livestock are responsible for 18 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. What would you say to someone who questions the role of livestock in reversing climate change?

- You spent 6 weeks at Zimbabwe’s Africa Centre for Holistic Management to learn more about this innovation and its success stories. How do the experiences with holistic management in the Southern Africa region relate to western rangelands of the U.S.?

- What are the challenges of and potential for integrating holistic management practices into development policies?

1. From your perspective, what is holistic livestock management and how does this idea challenge conventional grazing systems?

Holistic Management is a framework for making decisions that are economically, socially, and environmentally sound, and in essence, represents a new paradigm for people working in balance with nature. This framework deals with the complexity of natural resource management and is applicable to a wide range of contexts.

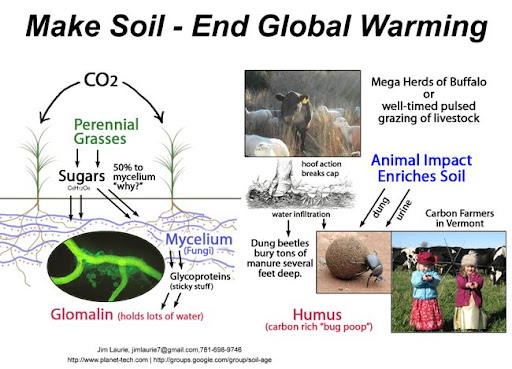

With regards to the care of land and livestock, for which Holistic Management is most cited, the practice seeks to restore grassland ecosystems by using livestock as a proxy for the wild herds of grazing ruminants, such as bison and wildebeest, that the great prairies and savannas of the world co-evolved with and depend on. These large animals, herding under the pressures of predation, and in a pattern that is unlike typical livestock management, are essential to plant grazing, soil churning, and nutrient and water recycling and distribution. It is the abundance, not the paucity, of these grass-eating creatures, moving in accordance with the rhythms of nature, that sustained the majestic grassland regions of most continental interiors. Thus, Holistic Management recognizes that fully functioning grassland ecosystems can not be sustained without herds of grazing animals.

It follows that desertification coincides with the removal of the natural impact of herding ruminants. Although much desertification is rightly blamed on poor ranching and agricultural practices, Holistic Management postulates that while these factors exacerbate the problem, they are not the root causes. Instead, the primary cause of desertification worldwide is the decimation of large herding animals (and their predators and cousin creatures), which have been driven to near extinction and in most cases exist, at best, as remnant herds. This constitutes a severing of the ecosystem, the impact of which is illustrated the world over. Wherever great herds have been eliminated, the prairies in which they used to roam, that flourished with tall grass, deep soil, and abundant surface water - if not now sustained with artificial fertilizer and irrigation - are becoming desert. This is true even in areas with little to no grazing. In fact, desertification, as severe as any in Africa, is occurring today in “protected” and “rested” wilderness areas managed by the US National Park Service, on land where there has been no livestock for decades (and of course, no impact from massive native herds). The land is drying and dying. This is not from too many animals, but from a lack of them. You can’t protect soil by denying it the ruminant impact it co-evolved with.

With the near eradication, by the 1890s, of 70 million buffalo, two million wolves, and four billion prairie dogs from the Great Plains, its ill fate toward dust bowls was set. Had agriculture or ranching never followed, the soils of the American Prairie were still destined to failure after this wholesale slaughter. Blame for the dust bowls is usually attributed to poor farming practices combined with drought, but the ecosystem health of this region was compromised a half century earlier when the removal of native wildlife became common practice. Holistic Management recognizes this and tries to restore ruminant impact to grasslands through the movement of livestock in a manner simulating the natural cycles of the great herds. This entails moving the animals in tight, agile groups, according to a grazing plan that stimulates plant growth, provides natural fertilization, and keeps the herds from returning to eat the same plants until they are fully re-grown, thus eliminating the overgrazing endemic to conventional ranching.

Some will argue that fire, instead of animals, can be used to sustain grasslands. Although true to an extent, it is a sleight-of-hand we pay a high price for. Fire has played a role in grassland evolution, of course, but it wasn’t until early humans began to systematically harness fire for clearing land for crop production that the territory of the grazers were infringed upon. Reliance on fire alone, as a tool to rid the land of each season’s growth, degrades soil over time while creating chronic environmental and health hazards. Historically, fires caused by lightning would have happened only in the short rainy season, a self-tempering process. In the dry season, under the bright blue skies, there are no fires from the heavens. During this arid time, the soil, in effect, is preserved in the guts of ruminants. We think that all soil is underfoot, but actually, ruminants carry the genesis of it with them. Grazers, not fires, make soil.

At the Africa Center for Holistic Management in Zimbabwe*, where I visited for six weeks, the use of fire to clear brush or recycle nutrients is discouraged. Instead, villagers are instructed in how to have these functions provided by animals. The general thinking is that grass should not be burned; it should become milk and protein. An expression I heard was “You can’t eat smoke.” In a land of hungry people, converting grass to smoke makes no sense. The grass should be eaten and manured by animals as nature intended, and in a way that builds soil and feeds people. This is possible. They are doing it.

*(The “Center” is a six thousand acre Holistic Management instructional ranch and learning site on communal lands in northwest Zimbabwe. The terrain is “high veldt”, or high desert, similar to northern New Mexico, with a mix of arid grassland and forested savanna ecosystems. There are no boundaries around the ranch and wild grazers and predators roam freely through it; these include buffalo, impala, elephants, lions, leopards, hyenas, and many others. There are five hundred head of cattle and several dozen goats. Livestock numbers are increasing as the ecosystem improves. When they began managing holistically about ten years ago, there were only about one hundred fifty cattle and the ranch was experiencing severe desertification. Today there is almost complete grass cover and a greater abundance of year-round surface water).

The challenge posed by Holistic Management to conventional grazing is profound. It recognizes that conventional grazing practices are unsustainable and lead to desertification and ultimately financial ruin. Unless livestock can be managed in a way that replicates the impact of native herds, there can be no long term future for ranching. The promise that Holistic Management provides, however, is of a ranching practice that can be viable, rewarding, and ecologically restorative.

The main challenge to ranchers will be in how their livestock are corralled and herded. The conventional approach essentially keeps livestock sedentary. They are not moved enough, leading to overgrazing, and are corralled in permanent fixtures that cause localized degradation. Both are unnatural. Holistic Management would have a plan that moved the livestock widely and prevented overgrazing, while additionally, moving the corral itself, never keeping the animals overnight in one place for more than seven to ten days. This has the effect of distributing the manure and plant litter to a degree that is beneficial, without the devastating impact of a central and permanent enclosure.

Of course, all this takes work, but new technology, such as mobile wire fencing makes it practical (in southern Africa they use canvas fencing for what they call the “kraal”, also called “boma fencing”).

Another challenge is to the idea that all that matters is how fat the livestock are. This is reductionist thinking. As discussed earlier, Holistic Management strives for economic, social, and environmental success factors. The weight of the cows is one factor, but so are the health of the land and the quality-of-life of the ranching families. Perhaps the cows are leaner because they got more exercise and were fed grass instead of grain, but because the animals and land are healthier, the ranch now spends less for irrigation, veterinary services, and pestilence control. The ranch owners are also healthier; they feel better about their product, and the ranch is viable so stress is reduced. By focusing on more than one variable, we can see improvements across all three. This is an example of what is meant by managing for complexity. Natural systems, like grasslands with ruminants, can not be managed with reductionist thinking. There must be a holistic framework.

2. What are the indicators for improved ecosystem health under holistic management techniques?

The many indicators of improved ecosystem health for grasslands under Holistic Management include: more grass cover, increased surface water, enhanced plant and wildlife diversity, and eradication of invasive or problem species.

Let’s look at these one at a time.

More grass cover: By this we mean an increase in the density of the plants, or, worded another way, a decrease in the space between plants. We could also describe this as decrease in bare ground, or, more dramatically, a reversal of desertification. It is all the same thing. In order to assess this, one needs to look down at the plants from above to see the space between them. In a healthy grassland system, there should be no space between plants at all – no bare ground. It should be hard, if not impossible, to see the ground. To do so, one resorts to kneeling and forcing plants apart at their base. Any water from the sky should land on leaves, not dirt. That’s how it should be.

Achieving this state using livestock is possible through Holistic Management, even in areas of low seasonal rainfall. When animal movement is done properly, plant growth is stimulated through grazing at the opportune time, soil health is enhanced with essential nutrients, and the land is “impacted” through hoof action, trampling plant litter and seeds into the ground along with manure to assure cover for new growth and moisture retention. As grasslands evolved with wild herds, the action of the entire herd was essential to the health of the ecosystem. Again, this was emphatically not just a few cows wandering about, overgrazing at their leisure, but massive herds, heavily impacting an area that was attractive to them (because the plants were at the right stage) -- eating, manuring, trampling, and then moving on, perhaps not to return for six months to a year or two.

Increased surface water: Increased surface water is one of the most important indicators of ecosystem recovery. In practice, in low, seasonal-rainfall grassland and savanna environments, the measure of surface water health that a land manager can readily see is how long springs or watering holes sustain into the dry season.

The improvement in surface water is explained as follows: When the soil is healthy, it is rich with organic matter that absorbs water, pulling it down and replenishing the water table. When soil is depleted, rainwater flows away, creating gullies and carrying topsoil with it. The erosion process can drain the water table. However, the opposite is also true. Improved soil health will replenish the water table. As this happens, the change in surface water will become apparent: streams and surface pools remain wet longer into the dry season and may also widen. Additionally, riparian areas will improve. Grass cover will extend to the edge of streams and there will be an increase in aquatic plants and animals, such as reeds and ducks.

At the ranch in Zimbabwe, surface pools appeared where they had never been before and lasted deep into the dry season. With these pools came waterfowl, crocodiles, and elephants seeking their bath.

All of these changes were noted after livestock density was increased several fold and holistic grazing was implemented. According to conventional environmental thinking, informed by literally thousands of years of livestock mismanagement, this outcome would be impossible. How can surface water improve with an increase in herd density? In a regimen of conventionally managed livestock, it would be impossible. However, in a regimen of holistically managed livestock, it is a logical and expected outcome. Surface water increases with the improvement of grass cover and soil health.

Enhanced plant & wildlife diversity: As grasslands recover, plant and wildlife diversity increases. This is driven by the changing biological composition of the soil – the plethora of bacterial and fungal communities that hide away carbon and exchange nutrients with roots. This soil community is enhanced by ruminant manure, which is loaded with water, minerals, and billions of essential bacteria that serve as “reinforcements” to their fellow microbes in the ground (particularly of importance in the dry season). As plants diversify, so will the bugs, birds and, ultimately, larger wildlife. Government park rangers in Zimbabwe observed there was a greater density of lions on the the ranch property than on the “protected” government lands where no grazing occurred. Although this statement sounds unlikely at first, the result is in line with the typical outcomes associated with sites where livestock grazing is managed properly: grass cover was enhanced and therefore the plant and animal diversity was increased; more wild grazing animals, such as impala, bushbuck, and kudu, came to the ranch and therefore the lions followed. (It should be noted that there are no permanent fences so wildlife can move freely).

Eradication of problem or invasive species: The eradication of so-called “problem” or “invasive” species is an industry unto itself. In the U.S., billions of dollars and countless hours are spent trying to poison, bulldoze, or burn undesired plant species out of existence. These efforts, however, are largely ineffective and can be counter-productive because they treat each species as a separate problem with its own eradication scheme. Also, in the U.S., custom arsenals exist for the destruction of everything from juniper, to mesquite, to prickly pear, to cheat grass. Never, or rarely, is it asked, “Could this be a soil problem, for which a soil improvement approach is warranted?”

Holistic Management, however, considers this. It recognizes that as properly timed grazing restores the grassland soils to their prior state, new conditions will favor the native species. Invasive species that had benefited from depleted soil will no longer be advantaged. As native plants return, so do the bugs, birds, and other smaller wildlife that help keep the ecosystem healthy. Additionally, livestock, including cattle and goats, can be used as tools to directly eradicate undesired species. For example, goats can eat prickly pear, and cattle can disrupt the life cycle of cheatgrass and trample and kill woody brush.

Although conventional grazing will often lead to an increase in woody brush, holistically managed grazing can decrease it. This is because in conventional grazing, the livestock, left to idly overeat plants, will avoid woody brush, thus benefiting the brush. Holistic Management, however, takes exactly the opposite approach. Animals are not permitted to overgraze, and instead of allowing them to tiptoe around the brush, cattle are intentionally herded right through it for the purpose of a disruption. They may even be corralled on top of a woody brush area, causing complete trampling and manure cover. This assures there will be new grass in the next rainy season. Thus, in a single year, a woody brush area can be converted to a grassy one. At the center in Africa, this practice is common, and large swaths of bare ground and woody brush have been converted to grass.

3. Why is holistic management significant to the issues of desertification and climate change mitigation and adaptation?

Holistic Management is central to the issues of desertification and climate change mitigation because it offers a natural solution for restoring grasslands, which are the largest ecosystem and one of the greatest stores of atmospheric carbon. Approximately one third to one half of all terrestrial carbon is stored in grasslands, a quantity on par with that stored in forests and in the atmosphere itself. The carbon stored in grasslands is many times the total amount of carbon added to the atmosphere since the age of industrialization began. This carbon is stored in the soil through root systems that can be meters deep. As soils degrade, carbon is lost to the atmosphere in a process that contributes significantly to overall greenhouse gas emissions.

Thus, grasslands are a linchpin ecosystem. If they continue to degrade to deserts, there will be no turning back global warming, even if fossil fuels are eliminated (because CO2 levels in the atmosphere will continue to rise, bringing us to dangerous thresholds). However, if grasslands can be restored, even partially, we have hope for large-scale carbon capture and climate stability.

The challenge for the climate change community, and environmentalists in general, is to realize that grasslands cannot be restored without the impact of herding ruminants that they co-evolved with. One way or another, large grazing animals, in significant quantities, are on the critical path to a livable future for humans on this planet. Either they will be wild herds, running in the presence of predators, or they will domesticated livestock managed entirely differently than usual, not as patrons at a smorgasbord, docile and overfed, but as proxies for their wild cousins – mobile, tightly grouped, providing essential nutrients, redistributing moisture, and living off the land in symbiotic balance with it.

When we understand that the work necessary to sequester excess carbon from the atmosphere is going to be provided not by humans, but by the photosynthesis of plants in concert with the microbial communities in healthy soil, then the role of Holistic Management as an essential climate strategy becomes clear. Without healthy grasslands there is no mitigation of climate change, and without thriving ruminant populations in balance with nature, there is no restoration of grasslands.

Allan Savory, inventor of Holistic Management, summarizes the climate impacting role of livestock in terms of the flow of both carbon and water. The way humans have traditionally run livestock tends to result in both carbon and water moving from the soil to the atmosphere. However, livestock managed properly changes the direction, resulting in both carbon and water moving from the atmosphere to the soil.

Holistic Management does not blame domestic grazers for desertification and global warming. It sees them as living resources that provide biological services and that’s impact on their terrain can either be destructive or restorative. It concludes, instead, the responsibility rests with people and the way we have made decisions regarding the use of these remarkable creatures. It recognizes that just as these animals were, through no fault of their own, part of the problem, they must also now be part of the solution. In short, there is no solution without them. Deserts will not green on their own. Soil needs ruminants.

4. Using cattle to mitigate global warming might seem counter-intuitive to many, especially in light of estimates that livestock are responsible for 18 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. What would you say to someone who questions the role of livestock in reversing climate change?

I would say they are right to be suspicious, because the history of livestock management has been deleterious and the modern behemoth of industrial livestock production is a major polluter of land, water, and air. But this predisposition, although understandable, misses the point about how ruminants are meant to interact with their grassland environments, and how livestock can, if we chose, be managed for restorative effects over vast expanses of deteriorating rangeland.

The phrase “livestock are responsible for 18 percent of greenhouse gas emissions” also underscores a profound misunderstanding. It is not the livestock that are responsible for these significant greenhouse emissions, but the fossil fuel intensive livestock industry. Any living creature is naturally in balance with it’s ecosystem, including all the minerals and gases that enter or leave it. The 18% figure stems from the 2006 UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report, Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. This report included all production related environmental impacts, such as fossil fuels, irrigation, grain, fertilizers, and land degradation. It also accounted for the methane problem of CAFOs where manure is held in anaerobic lagoons. It is a proper indictment of the fossil fuel livestock industry, which is indeed destroying land and contributing to global warming.

This report, however, has nothing to do with animals living in balance with their surroundings, nor with Holistic Management, the whole point of which is to help stop the degradation of industrial livestock production and restore grasslands to health through proper ruminant action. Seeing as Holistic Management uses range-fed cattle that are managed for ecosystem recovery (and thus carbon capture), none of the numbers associated with FAO report are germane. They are entirely different systems. The only thing that is common is the cattle, and cattle aren't the problem: the industry is, and that must change. Holistic Management provides a model for what that change could look like, and it would be helpful for future assessments to consider this option. Range-fed cattle that are managed for ecosystem recovery will be helping to enhance grass cover and build soil and thus will actually be carbon negative. This will be true until such a time that the soil is maximally restored. That could be decades or centuries.

It’s important to remember that ruminants evolved to be in balance with grassland ecosystems, playing essential roles is maintenance of plants and soil health. CO2 atmospheric loading in the case of industrial livestock does not come from the animals, but from fossil fuels and improper land use. Those are human induced ills that can be changed. Additionally, the methane released by ruminants should be balanced by the intake of methanotrophic bacteria naturally present in healthy pastures. Finally, manure should in the fields, building soil, not in anaerobic lagoons. The conclusions of the FAO report should be a call for us to the right thing, and that is to stop growing grain for cattle and to restore livestock to their proper place as soil-enhancing ruminants. The potential of carbon capture via grassland restoration is enormous, and without proper ruminant action, either through wild herds, or livestock managed as a proxy, desertification will continue and this opportunity for carbon capture will be lost.

Many practitioners will posit that not only is Holistic Management essential to reverse desertification, but it is the only means available to restore enough of the world’s prairie and savannas fast enough to avoid a climate catastrophe. I find this a compelling argument.

5. You spent 6 weeks at Zimbabwe’s Africa Centre for Holistic Management to learn more about this innovation and its success stories. How do the experiences with holistic management in the Southern Africa region relate to western rangelands of the U.S.?

The experiences of Holistic Management in southern Africa relate to the western rangelands in the U.S., because the biomes are quite similar, as are the needs and goals of the ranchers and agriculturists in both regions.

The vast interior expanses in Africa and America, and also Asia and Australia, where grasslands and grazing herds co-evolved, and where most the world’s agricultural products are produced, are all subject to similar trends towards desertification. The removal of natural ruminant action combined with overgrazing and poor farming practices (including the overuse of fire), diminishes the soil, reduces yields and contributes to global warming.

Yet, just as grasslands everywhere are susceptible to degradation, so too are they responsive to regimens of repair. The successes in southern Africa show that even in the world’s most impoverished areas, where the mismanagement of land and livestock has created high rates of desertification, reversal of fortunes is possible. Using livestock as a restorative tool -- with well planned movements, grazing, and corralling -- can increase the grass cover, improve the water cycle, and provide viable livelihoods for land managers and their communities. If it can happen in southern Africa villages, it can -- and does -- happen on the American ranch.

It should be noted here that Holistic Management is already widely practiced in America and has been for decades. The Savory Institute in Colorado helps facilitate training and implementation, and a new organization, Grasslands LLC, provides an outsourced ranch management service utilizing Holistic Management practices. Holistically managed ranches exist in many states (including Texas, Virginia, Vermont, New Mexico, Missouri, Colorado and elsewhere). The land healing success repeatedly demonstrated in various climates and conditions provides clear evidence for the restorative capacities of this approach.

On a personal note, what I found most revealing was the story from one Zimbabwean village woman about how, in the past, before holistic management practices were begun, the presence of biting ants made walking in the field intolerable. People without shoes had to wear plastic bags on their feet. The ants also attacked the baby goats and birds. It was horrible. Authorities told villagers the only treatment was expensive chemicals. However, once holistically managed grazing was started and the grass cover improved, the ant problem vanished. This is an invasive species issue, as discussed earlier, but it’s also much more than that. It’s a human story, and people anywhere will want to benefit from healthy land. It doesn’t matter what continent you live on. Nobody wants biting ants on their feet.

6. What are the challenges of and potential for integrating holistic management practices into development policies?

The potential for integrating Holistic Management into development policies is enormous and grows as the failures of our current models become more apparent and costly. The ranch in Zimbabwe, serving as both a demonstration site and learning center, hosts a steady stream of representatives from development NGOs who are eager to learn about Holistic Management and put the tools into practice. They are looking for solutions that are practical, affordable, and that can simultaneously address the multitude of issues that accompany land use decisions. There are pilot projects throughout Africa and growing interest for major efforts throughout Zimbabwe, Namibia, Kenya and South Africa.

In January 2013, a conference on Holistic Management (“Creating the Future We Want: Holistic Solutions to Global Challenges”) will be hosted by the Center for International Environmental Resource and Policy (CIERP) at the Fletcher School at Tufts University. In addition to showing the benefits of holistic land and livestock management, this conference is intended to show that the holistic framework for decision making can be used in any situation involving the management of complexity, as do all development projects and policies. As the Fletcher School at Tufts University is one of the leading international policy formation institutions in the world, this will be an important opportunity for Holistic Management to gain wider exposure and influence.

Regarding the challenges to integration of Holistic Management into development policy, it appears to me that these are threefold. They are 1) the fragmentation of traditional policy formation, 2) the frequent misrepresentation of Holistic Management in academic literature - often associating it with rigid grazing systems, and 3) the reticence of policy institutions to entertain any policy that includes livestock as a “solution”. Although each is a formidable challenge, there is encouraging progress on all fronts.

6.1) Fragmentation of Policy Formation

The first challenge is the fragmented nature of policy formation that channels expertise and funds toward isolated goals, often exacerbating the problem trying to be fixed or causing worse unintended consequences elsewhere. Land use, water use, climate change, desertification, crop production, development, health care, poverty, conflict resolution and avoidance, etc., are each treated separately within its own bureaucracy.

In the case of international policy formation, this fragmentation is even legally obligated, where it is stipulated that one development policy cannot overlap on the province of another. This imposes a piecemeal framework on nature and makes integrated solutions difficult. In other words, we are applying the “machine model” of individual parts to a natural system in which the mutualism of diverse elements is the norm and where emergent behaviors through complex interactions are inherent and unpredictable.

Recognizing this, the holistic framework enables policy makers to address social, economic, and environmental complexity in a single context. When a range of development issues can be dealt with in unison, the prospects for Holistic Management integration are enhanced.

6.2) Misrepresentation of Holistic Management in Academic Literature

The second challenge to implementation is the frequent misrepresentation of Holistic Management in academic literature. Often it is incorrectly associated with more rigidly programmatic grazing systems, such as rotational grazing or pulsed grazing, the failed outcomes of which should not be surprising. Holistic Management itself, however, is not a grazing system, although many have borrowed from it. The recognition that higher cattle densities and more frequent movements must be part of the solution to replicate native ruminant impact, is often misconstrued to be the totality of Holistic Management, when, in fact, those are simply outcomes of the planning process. Rotational, pulsed, high-impact, or any other “system” attempting to simplify the planning process or reduce it to an Extension Service rule-of-thumb, is not Holistic Management.

As stated earlier, Holistic Management is a framework to help land owners manage complexity to make decisions that are economically, socially, and environmentally sound. This technique evolved out of military decision-making tools (called “aide-memoires”) used by officers to help make crucial decisions during battle. Allan Savory, exposed to these tools while serving in the Rhodesian military, later realized they could be generalized to work in any situation with multiple complex interactions, and thus applicable to help ranchers. Holistic Management, therefore, is not a grazing system any more than the military aide-memoire is a battle system. Both are just tools for making decisions in the face of complexity.

In the military case, the parameters may have included the number of troops, the quantity of provisions, and the position of the enemy. In the land and livestock case, relevant parameters include the number of cattle, the quality of paddocks, the calving schedule, the wildlife and biodiversity needs, and the placement of water. In each case, though, there is a goal. In the military case, presumably, to win, but in the land and livestock case, to have healthy animals, productive land, and viable enterprise. You can’t predict how long the cattle will be in each paddock until all the parameters are identified and put into the tool, and you can’t transpose one ranch’s grazing schedule to another. Every situation is different, and the aide-memoire is continuously updated. Simply introducing concepts such as “pulsed” or “rotational” to any grazing system doesn’t provide the landowner with a plan formulated to achieve the desired results on their specific parcels given their specific circumstances.

This distinction, however, of Holistic Management as a decision making tool versus a grazing system, is apparently challenging for academia, and so it is often overlooked, at great disservice to the ranching community. An avalanche of papers that rightly find no meaningful difference between one grazing system or another, or that correctly show that increasing livestock density (without Holistic Management) increases land degradation, are nonetheless used as evidence against Holistic Management. How one paddock study that simply changed a single parameter (such as herd density), but made no effort to use the decision making tools that account for the full complexity of the ranch (including the animals, the grass, the water, the seasons, and the goals for the ecological recovery), could then claim to be representative of Holistic Management, presents a stretch of logic few in the Holistic Management community can fathom.

The only apparent explanation for this, is that range scientists are trained to do small scale paddock studies, changing one or two variables chosen ahead of time. So, that’s what they do. Livestock movement in these studies are not orchestrated with a goal toward ecological recovery and they have no adaptive capacity to modify their schedules over time in response to changing conditions. Thus, nothing about the results are surprising. They tell us what we already knew, that prescribed grazing systems don’t work. It can be logically assumed, that if you don’t have a goal for ecosystem recovery, you aren’t going to get it. No one questions that there are many ways to degrade land via grazing. Humans are quite expert at that. We are also quite expert at degrading land by leaving it alone, by denying it its necessary herd ruminant impact, and by letting it dry out and turn to shrub and sand, as is the case on “protected” arid land around the world. The more interesting and pertinent question is, are there ways to restore it? Are there examples of land getting healthier? Were livestock involved? If so, where, and how were they managed?

Renewed investigation into Holistic Management will help provide answers to these questions. Although the initial phase of research was flawed (by its wrongful association with grazing systems), it appears the science is evolving and new studies are being designed appropriately. Investigators are beginning to understand that a paddock study of the old type is inappropriate, and that studies must be done at the ranch scale, over several years, and on a property where the owners are managing with adaptive holistic methods and towards clearly articulated ecological recovery goals. Ranches around the world, including the center in Zimbabwe, are demonstrating recovery and viability, to the great satisfaction of their owners, so it is only a matter of time before the body of scientific evidence is properly balanced.

Fortunately, the balance is close at at hand. Some of the range scientists who are investigating holistically managed properties include Don Nelson of Washington State University, Richard Teaque of Texas A&M University, Fred Provenza of Utah State University, Debora Stinner of Ohio State University, Rigoberto Alfaro-Arguello of El Colegio de La Frontera Sur (Mexico), and Stewart A.W. Diemont of State University of New York. Their work is highly informative and deserves wider attention - providing glimpses into what is possible. Don Nelson, for example, has shown that holistically grazed property in the Toulouse region of Washington State has better ecosystem indicators than the adjacent, and “resting” Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) land. The results support the adaptation of this grazing approach both for land coming out of CRP, as well as for an alternative to CRP itself. Although CRP is hailed as ecologically smart, because it temporarily halts the destruction of commercial farming, it’s clearly not the best we can do. As the native grasses on the land evolved to be grazed, it’s not surprising that a plan that replicates that action, would have better recovery results than just letting the land “rest”. Land doesn’t want to “rest”. That’s a human projection. If it were a native grassland, what it “wants” is ruminant impact, including grazing and manuring. The drier the land, the more this is true.

Detailed case studies, including names, places, land types, practices, results, etc., are also explored in several books, including Gardeners of Eden by Dan Dagget (2005) and For the Love of Land by Jim Howell (2009). As one example, grazing practices on the U Bar Ranch on the Giles River in southwestern New Mexico, have turned it into the home of one of the largest population in the country of the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher. In fact, the flycatcher population on the ranch far exceeds the population in the adjacent “protected” bird area managed by the U.S. Forest Service. The flycatchers are thriving, in part, because of the grazing practice, which is managed for riparian recovery, and not in spite of it. The scientific community is certainly able, and highly encouraged, to follow up on this and other success stories.

Furthermore, at least one rancher, Chris Gill, owner of the Full Circle Ranch in West Texas, has published his own case study out of frustration at the range science and policy community that ignores evidence of recovery. Gill claims the implementation of Holistic Management has allowed him to triple the number of animal grazing days recommended by local extension services, while at the same time increasing forage production by 35%. In other words, he has improved his land with grazing. What matters is not that he simply has more livestock, but that he is managing them according to a plan for recovery. Chris has gone to great pains to document his ranching practices and share them with the scientific and lay communities.

Finally, and with great anticipation, a 5-year study being administered by the South African Agricultural Research Council, is just embarking that will monitor land at the center in Zimbabwe and on adjacent forest service parcels that are part of the same catchment. Some of the land they will be monitoring (that I’ve seen) is thoroughly degraded from many years of “rest” (no grazing, minimal impact from wild herds). It will be exciting to see this land recover, as it certainly will, with healthy grass replacing bare ground, and dry stream beds once again flowing with clear water. The results from that study should remove any lingering doubts about the efficacy of Holistic Management.

6.3 ) Reticence of Environmental Institutions to Entertain any Policy that Includes Livestock as a “Solution”

The third challenge, influenced by the second, is the reticence of influential environmental institutions to entertain any policy that includes livestock as a “solution”.

This position is understandable, to a point, given the track record of livestock’s negative impact on the environment for hundreds and possibly thousands of years, and of course its greatly expanded impact in modern times. No one questions the irrefutable evidence of land degradation that has accompanied livestock handling in every corner of the globe. Particularly not questioning of this, are practitioners of Holistic Management, whose strategy is specifically to help restore degraded lands.

The paradigm hurdle that most policy institutions have yet to clear, is that the same creature that contributes to the erosion of soil, can also be used for its restoration. Practitioners and advocates of Holistic Management take this argument one step further, positing that proper herding of livestock is the only strategy that can restore significant expanses of the world’s degrading rangeland quickly enough to reverse widespread desertification and prevent a full-blown climate catastrophe.

Allan Savory has said, “We will not be able to address climate change using the only tools that science is considering, and the entire future of humanity, and of civilization as we know it, hangs on the slender thread of learning how to manage livestock properly to mimic nature.”

Counter-intuitive as this assertion may at first sound, after several years of inquiry, I fail to find fallacy with it. You could ask, what about the wild herds and their predators? Can’t they restore the grasslands that will sequester atmospheric carbon? The answer is yes, they could, but that isn’t a realistic solution. We aren’t overnight going to have 70 million buffalo, two million wolves, and four billion prairie dogs on the Great Plains of the U.S. Nor are we going to resurrect immediately the unfathomably large herds that used to run freely across Africa and Asia. Nor would doing that help humans meet their protein or agricultural needs.

Neither are we foolhardy enough to believe that petrochemical fertilizers and irrigation are going to meet the needs of humanity without being ruinous to soil and climate. Nor is the miracle cure, biochar, going to be applicable on billions of acres of denuded lands, many far removed from people. Although expanding wild herds must, of course, be part of the plan for ecosystem recovery, it isn’t good enough, and wont be effective if we continue to mismanage livestock.

We need a realistic solution in which humans manage their livestock in balance with nature, in a way that helps wild herds as well as people. A practical example of this would be the gradual decommissioning of feedlots. Instead of simply imagining that the cattle “go away” or that somehow feedlots become “green”, the enclosed cattle could be freed for part of their stay, through a carefully managed plan, to help restore adjacent degraded land. This would reduce the livestock’s dependence on costly grain while helping to grow more grass for future grazing, benefiting domestic and wild animals. (A plan to use this method to restore the Teel's Marsh area of Nevada has been presented to the Bureau of Land Management and has been written about in the aforementioned Gardeners of Eden).

The beef industry isn’t just going to end. It needs to be transformed. This is one approach that offers promise for both restored land and healthier food. The moment we shift our collective mental rudder toward a worldview that includes properly managed livestock as a tool for restoration, is the moment previously intractable problems cease to be quandaries and we are on course toward a hopeful future. Esteemed policy institutions, such as Worldwatch, can be leaders in this transformation.

- admin's blog

- Log in to post comments