You are here

Fletcher Presentation: Reversing Global Warming and Desertification with... Livestock?

On January 25th I spoke at Tufts University regarding Holistic Management and my experiences in Africa. Below is their writeup.

http://fletcher.tufts.edu/CIERP/News/more/Jan25Itzkan

Reversing Global Warming and Desertification with... Livestock?

January 25, 2012

Using cattle to reverse desertification may sound counter intuitive, and rightly so; nonetheless, the Africa Center for Holistic Management (ACHM) in Zimbabwe is doing just that, using livestock to improve both grass cover and water cycle. Seth Itzkan, president of Planet-TECH Associates, a consultancy that investigates trends and innovations, recently spent six weeks with the ACHM where he saw first-hand how livestock are being used to restore depleted grasslands, and in the process improving the livelihoods of local villagers. This practice also has import for climate change, because even slight replenishment of grassland soils would sequester significantly quantities of atmospheric carbon.

At Fletcher, Itzkan recently gave a presentation on Reversing Global Warming and Desertification with Livestock. “This topic is galvanizing to say the least,” said Itzkan in his opening comments. He then continued, “but there’s an innovation in terms of how livestock are being managed which I think is essential for us to know about.” He explained that this innovation “has to do with using (livestock) in a way that simulates the herd impact that the grasslands evolved with.”

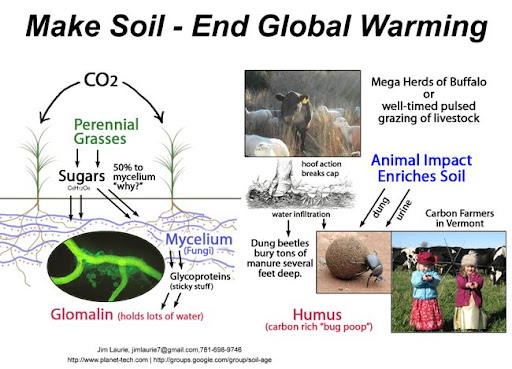

“Throughout America and southern Africa, massive herds of grazing animals were essential to the health of grassland plants and soils,” said Itzkan. “These great herds have been decimated the world over,” he added. Itzkan explained that in America, for example, the native population of 35 to 70 million buffalo was nearly driven to extinction. “Grasslands are dying in part because of this severing of the ecosystem – removing large herbivores from the plains they evolved with,” he said. This impacts climate change, explained Itzkan, because grasslands are major stores of atmospheric carbon. When they are healthy, they will sequester carbon into the soil via their roots, but when they dry up, they release it.

According to Itzkan, practitioners of Holistic Management (also called Holistic Planned Grazing) believe that wild herbivores, and their domestic cousins, if properly managed, can restore grasslands to their former health and productivity. With livestock, this is done by moving them in a fashion similar to how wild herds behave in the presence of predation – closely packed and continuously moving, without overgrazing. “Overgrazing is a human invention,” stated Itzkan. “Natural herds don’t overgraze,” he stated. “Why would they?”

Itzkan pointed out that the essential role of the larger herbivore has been lost in our understanding of how grasslands survive. He said that when grazing lands in seasonally dry areas show signs of desertification, the standard response is just to reduce the number of grazing animals, or, as it is officially called, to “destock.” “But over time that doesn’t help,” said Itzkan, adding that “the land continues to undergo desertification.” Test plots in the American southwest that haven’t had grazing in decades are still turning to desert, explained Itzkan. “The animals help make the soil,” he said, adding, “The grasslands need animal impact.” The loss of the great herds on the US plains, explained Itzkan, was the beginning of the end for much of that ecosystem.

Holistic Management is an important innovation because “it looks at the whole ecosystem,” said Itzkan. “They’re trying to restore a type of balance in terms of how the land is impacted in the absence of the herding herbivores that grasslands used to have,” he added. Itzkan explained that this approach, invented by Allan Savory, a former Game Ranger from southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), seeks to reverse desertification by simulating the herd impact that kept savannas healthy in the first place. “This is being demonstrated in Africa without the use of irrigation, seeds, or heavy machinery. The only ‘tool’ is livestock.” The results, said Itzkan, are “counter-intuitive,” explaining that they are seeing improvements in grass cover, biodiversity, and water cycle, all while increasing herd density and expanding accommodations for people.

While discussing the specifics of Holistic Management, Itzkan said that they have a formal planning process that is able to accommodate complexity. “This is the key intellectual difference,” stated Itzkan, from ‘grazing systems’ that move cattle according to a simplistic and non-adaptive plan. “A lot of range scientists are missing this distinction for some reason,” stated Itzkan, adding, “It’s not just numbers, it’s the management.” Itzkan explained that part of that management includes the regular moving of the corrals to cover bad spots or crop fields with dung, urine, and litter (grass, leaves, twigs, etc.). This is then followed with a grazing schedule that is tailored to local conditions. “Obviously if you just increase herd density and continue to let livestock wander, the grass is not going to recover,” stated Itzkan. “There is a management process here and quite frankly it takes a lot of work. You’re trying to simulate something that nature would have done on her own, integrating many different variables.”

Itzkan shared photos and videos taken during his Africa trip, and elaborated on several specific success stories, one of which was his tour to the Dimbangombe River, south of Victoria Falls. He recounted how a 1.7-kilometer long stretch of the river now has more water in the dry season than it has had since records were first kept decades ago. They now have surface water for cattle year round, explained Itzkan, something they never previously had. “The land is actually retaining more water with the increased grass cover,” explained Itzkan. Itzkan also showed photos taken from a fixed transect site over a five-year period from 2002 to 2007 that demonstrated barren land being restored with healthy grass cover. “The only tool was livestock,” Itzkan re-emphasized. Finally, Itzkan showed pictures and stories from the villages where the program is active. According to Itzkan, one lady explains that previously there was much bare ground and an infestation of biting ants. Those without shoes had to wear plastic bags on their feet. After several years of proper livestock management, the grass cover improved and the ant problem went away. This example, Itzkan said, could be a “microcosm of the world.”

At the conclusion of the talk, Bill Moomaw, Director of CIERP, said that Holistic Management could simultaneously address the three major policy challenges of climate change: development, mitigation, and adaptation. “It does it all,” he stated, adding, “It meets the livelihood criteria, it meets the adaptation criteria, (and) it meets the mitigation criteria, (so) why shouldn’t we try to do that? We need an integrated sustainable development strategy.” Acknowledging the unique but compelling nature of this approach, he thanked Itzkan for “bringing these unconventional, challenging ideas to our attention.”

- Seth's blog

- Log in to post comments